IRISH EMIGRATION AND ARRIVAL IN

COLONIAL AMERICA

WILLIAM MONTGOMERY (1675 - 1731)

John and Isabella Shaw had at least three sons named Hugh b 1657, Robert b 1661, and William b c. 1661, presumed in that order. It would not be unusual for the son Robert, when he grew his own family, to follow his father John's naming of his own sons: WIlliam b 1675, Robert b 1685, and Hugh b 1689. So there they were, at the beginning, the three brothers and their families, together with their father, Robert, and mother Mary Eliza (McCullom), and perhaps some sisters and their families . . .So, there they were at the beginning, in Ireland, before they left, the Montgomery brothers, all part of same group which would go to a new world . . .

In the Spring of 1718, a body of Scotch-Irish from Northern Ireland sent a petition, signed by 319 representative men on 26 March 1718(1), to Governor Shiite of Massachusetts Bay in the New World requesting land for settlement. Governor Shute was in the third year of his administration of the colony. He was an old soldier of King William, a Lieutenant-Colonel under Marlborough in the Queen Anne Wars and had been wounded in one of the great battles in Flanders. The Rev. William Boyd was dispatched from Ulster to Boston, with the petition, as an agent of the Scotch-Irish to express their desire for settlement in New England.

The petition read as follows:

"We whose names are underwritten, Inhabitants of ye North of Ireland, Doe in our own names, and in the names of many others, our Neighbors, Gentlemen, Ministers, Farmers, and Tradesmen, Commissionate and appoint our trusty and well beloved friend, the Reverend Mr. William Boyd, of Macasky, to His Excellency, the Right Honorable Collonel Samuel Suitte, Governour of New England, and to assure His Excellency of our sincere and hearty Inclination to Transport ourselves to that very excellant and renowned Plantation upon our obtaining from His Excellency suitable incouragement. And further to act and Doe in our Names as his prudence shall direct. Given under our hands this 26th day of March, Anno Dom. 1718."

Excerpt From: The Scots-Irish: The Thirteenth Tribe, by Raymond Campbell Paterson

The Real Cause of the Emigration:

"The Ulster Presbyterians had endured, and survived, past waves of religious discrimination, and would most likely have continued to thrive in the face of official hostility. But in the early years of the new century they were faced with an additional challenge, one that threatened the whole basis of their economic existence in Ireland. By 1710, most of the farm leases granted to the settlers in the 1690’s had expired. New leases were withheld until the tenants agreed to pay greatly increased rents, which many could simply not afford to do. Rather than submit to these new conditions, whole communities, led by their ministers, began to take ship for the Americas. A new exodus was about to begin.

In 1719, the year after the first great wave moved west, Archbishop William King wrote an account of the migration from Ulster, pinpointing the real source of the upheaval:

“Some would insinuate that this in some measure is due to the uneasiness dissenters have in the matter of religion. But this is plainly a mistake, for dissenters were never more easy as to that matter than they had been since the Revolution [of 1688] and are at present, and yet never thought of leaving the kingdom till oppressed by the excessive rents and other temporal hardships. Nor do any dissenters leave us, but proportionally of all sorts, except Papists.

The truth is this: after the Revolution, most of the kingdom was waste, and abandoned of people destroyed in the war. The landlords, therefore, were glad to get tenants at any rate and let their lands at very easy rents. They invited abundance of people to come over here, especially from Scotland, and they lived here very happily ever since. But now their leases are expired, and they are obliged not only to give what they paid before the Revolution, but in most places double and in many places treble, so that it is impossible for people to live or subsist on their farms.”

There was much to be done by a family before removal to America. A supply of food, clothing and bedding was necessary and the household goods had to be packed for the long voyage. The land, farm animals, and the heavier tools must be sold. These were busy days and the partings must have been hard on all, unless friends hoped to follow soon or be along on the same journey. In leaving their Churches the emigrants did not fail to procure testimonials of good standing to be used in forming fresh religious ties in New England. (Bolton)

A 45 ton vessel of this time carrying 100 passengers plus crew would be CROWDED. The only place on a ship of this size with a bunk would be the captain's cabin. Everyone else would have a hammock, if lucky, a place among or on top of cargo or food supplies, if not. 100 people in a 45 ton ship, which would be approximately 55 feet long excluding bowsprit, would leave no room for a real cargo, though. There would be low headroom below deck. For cooking, as the gimbaled stove had not been invented, there would have been a brick stove below decks, which could only have been used in calm weather. There could conceivably have been weeks at a stretch with no hot food. As for the food, there are lots of old seafaring novels which describe this fairly accurately. Before the 20th century ship- board food did not change much. In heavy seas or storms the entire area below decks would be dripping wet. If there was much wind, most of the passengers would have been required to stay below deck; they were part of the ballast. The length of the trip would have varied immensely, from less than a month in ideal conditions to three months.

The Irish ships began arriving in America in July, 1718. William and his brothers, Hugh and Robert, sons of Robert Montgomery, grandsons of John and Isabella Montgomery of Aghadowey, Ireland, were aboard some of the five ships which sailed into the little warf at the foot of State Street in Boston, among one-hundred and twenty Scotch-Irish families from Northern Ireland.

Ships recorded as arriving from Ireland in 1718, as recorded in the “News-Letter” newspaper in Boston, include:

Week of July 21- 28 - The “William & Mary”, James Montgomery, Master. (Aboard was the Reverend William Boyd of Macosquin, with “news of many families coming”.)

- Week of July 28- Aug 4 - The “(unnamed ship)”, John Wilson, Master, with “200 souls aboard”

- August 4 - The Brigantine “Robert”, James Ferguson, Master, including Rev. James MacGregor, Hugh Montgomery, Sr. and many others

- August 4 - The “William”, Archibald Hunter, Master, from Coleraine

- August 4 - The “Mary Anne”, Andrew Watt, Master, from Dublin

- September 1 - The "Maccullom" (McCullom), James Law, Master, from Londonderry with “20 odd families - and linen"

- September 1 - The “William”, the “Elizabeth" with passengers and provisions, the “Mary and Elizabeth" at 45 tons with 100 passengers and linen (R.J. Dickson, 1966), and the “Dove" at 70 tons

- September 4 - The “Pink Dolphin”, John Mackay, Master, from Dublin

Later in the fall of 1718, after late October, the ship “Robert" would sail up from Boston into Casco Bay where it became lodged in the ice while quarantined due to smallpox onboard the ship. All aboard spent an entire winter in most the deplorable conditions aboard the ship. This ship most likely included the Reverends MacGregor, McKeen, Cornwall and their followers.

Boston was a town of approximately 12,000 people at this time. Many of the families were natives of Scotland whose heads had passed over into Ulster during the short reign of James II. Several of these families were well off, including the Cargills, who had cousins Jean (Hugh Montgomery) and Mary (John McMurphy) arriving on the ships. These families, or their fathers and neighbors, had felt the edge of the sword of Graham of Claverhouse in Argyleshire, Scotland (Scotch-Irish Society, 1889).

Others in the body were the descendents of those who had participated in the original colonization of Ulster dating from 1610. Still others included descendents of those Scotchmen and Englishmen that Cromwell transplanted at the middle of the century to replace those wasted by his own sword. A few native Irish families were also mingled in. They were escaping the economic and religious oppression there and the fear of their lives from the warring religious factions.

One motive of Massachusetts in providing settlement lands to the Scotch-Irish was to have them settle on the frontiers (in Maine, among others) as a living shield against the French and the Indians. The motive of the Ulstermen in coming to New England was to be free to worship as they saw fit and to establish homes and commercial activities with less government control and ownership of the land.

The Scotch-Irish emigrants were offended at being called 'Irish' because they had frequently ventured their lives for the British Crown against the Irish Papists(4). The people in New England did not understand the distinction and it was some time before they were treated with common decency. Inter- marriage among the Scotch- Irish families was very common for the first few generations because of the ill- treatment that they received from established settlers.

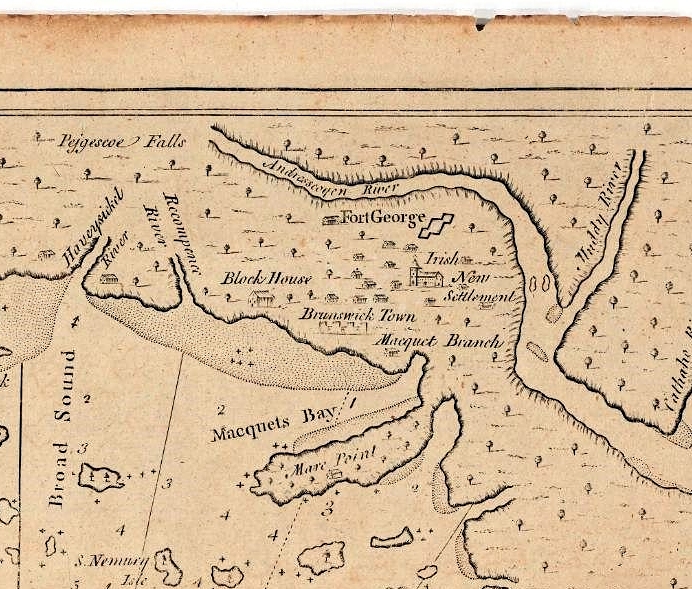

A Captain Robert Temple came over to Boston with his family and servants in the autumn of 1717 to settle as a gentleman farmer. He visited Connecticut and also the lands of the Pejepscot Company about the Androscoggin River in Maine. He much preferred, however, the lands on the east side of the Kennebec, opposite the mouth of the Androscoggin. Upon his return to Boston he was taken into the enterprise, and agreed to undertake the transportation of settlers from Ireland.

Robert Temple engaged two large ships in 1718, and three more ships were chartered the next year. The Scotch-Irish whom he brought over settled on the east bank of the Kennebec, between the present towns of Dresden and Woolwich. The land was called Cork. The names of some of his people were: William Montgomery, --- Caldwell, James Steel, David Steel, --- McNut, James Rankin, William and James Burns or Barns. A few of the Robert Temple colonists settled in Topsham, opposite Brunswick, and several in Cathance, now part of Bowdoinham, on the Kennebec, south of Dresden. Others, the larger part of the several hundred who came under Temple, went to New Hampshire and Pennsylvania to avoid the wrath of Father Rasle and his Indians. Cork was destroyed soon after.

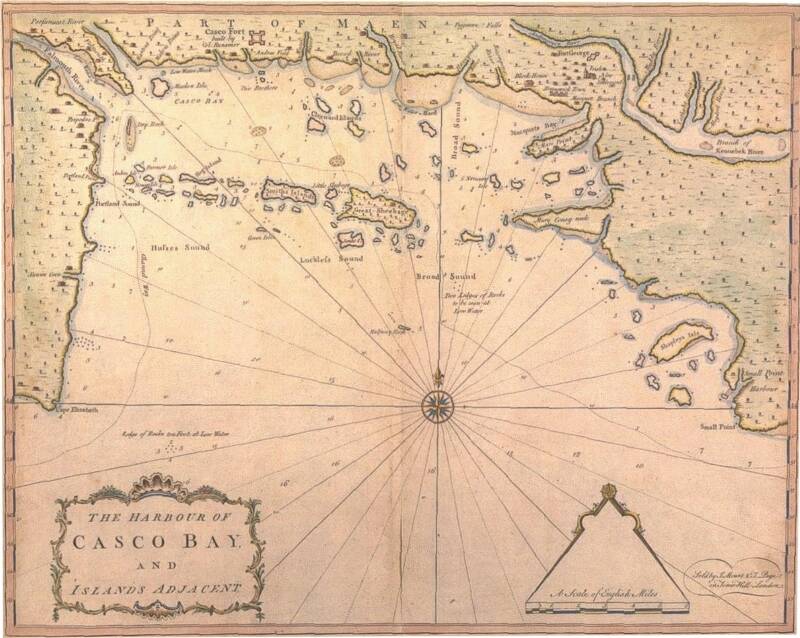

William and Mary Aiken Montgomery came to America with their children on the ship "MacCullum". They had departed Londonderry three months earlier. The emigrants aboard the five ships to arrive in September, 1718, at Boston included most of the Presbyterian Congregations of Macosquin, Aghadowey, Garvagh, and Kilrea along with people from Ballymoney, Macosquin and Coleraine. They helped establish “the new Irish Settlement" with Rev. James Woodside of Garvagh of the Bann Valley, Northern Ireland. See Cyprian Southack's 1720 map of Merrymeeting Bay, the place called Cathance, which in 1910 was called Bowdoinham (Bolton). Among others aboard the ship MacCullom were: (?) Caldwell, James Steel, David Steel, and (?) McNutt. It is quite possible that one of these "Mr. Steels" became the husband of Margaret, the daughter of William's brother, Robert.

The Irish ships must have brought immigrants rapidly, for Southack's map of Maine, published in London in 1720, states that already five hundred had arrived, or about one hundred families. The Boston News-Letter for August 17-24, 1719, prints an item from Piscataqua, Maine, dated August 21st, to the effect that Philip Bass had arrived at the Kennebec River from Londonderry with about two hundred passengers. Many of these must have been friends of those who came in the Maccallum (McCollum), one year earlier.

William and Mary and family lived in the Merrymeeting Bay area of Maine for not even two years, then removed to Hopkinton, Massachusetts, following drastic events in conflict with native Indians. They removed to Massachusetts and were in Hopkinton by 1720.

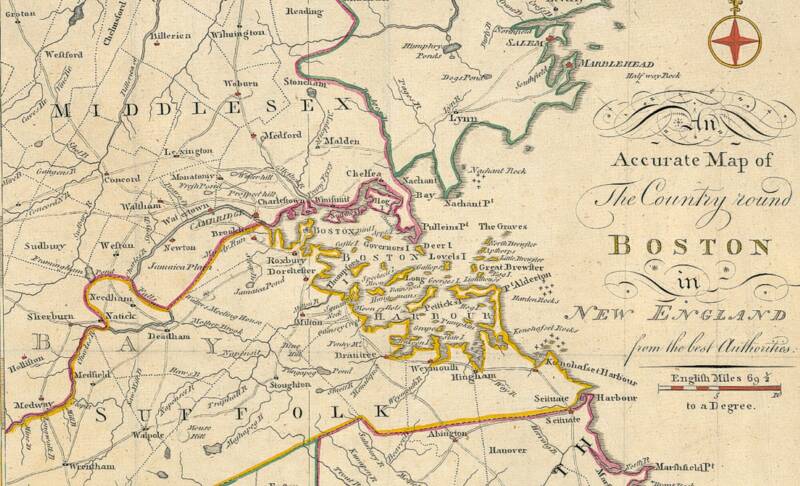

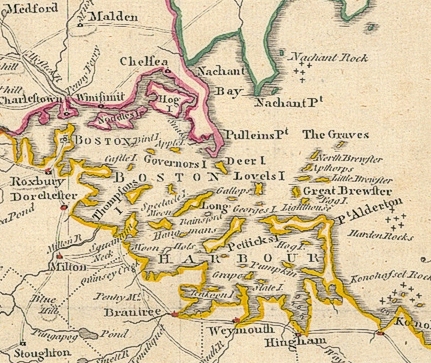

William and Mary and family settled in Hopkinton, MA, just west of Boston. (Hopkinton is center left, just off the above map) On September 2, 1724, William Montgomery was one of fourteen men who, with pastor Rev. Samuel Barrett, established the First Congregational Church at Hopkinton. In 1728, Rev. Samuel Barrett officiated the wedding of William's daughter, Abigail, to John Harper in (Christ Church) First Congregational Church of Hopkinton, MA. And then came "trouble" for the Scotch Presbyterian-oriented members of the young First Congregational Church in 1732 . . . see notes for William's son, James Montgomery.

In the Spring of 1719, some of the other emigrants, including Rev. James MacGregor and his followers, including Rev. Cornwall, received Deed to land about 30 miles north of Boston. The deed was given to Captain Cargill (father of Hugh's wife) and over a hundred others. Together, they founded the town of Nutfield at that location. Later they changed the name to Londonderry. Today, it is called Derry, N.H. They settled in this area under the leadership of the Reverend James MacGregor, their Pastor in Aghadowey. The deed was dated Oct. 20, 1719. They named this land, "Nutfield". Rev. MacGregor settled in Londonderry, N.H. and died there Mar. 5, 1729. Rev. MacGregor was married to Marion Cargill. William's brother, Hugh Montgomery, had the Rev. MacGregor as his pastor and was married to Jean Cargill. Jean, Mary (MacGregor) and Marion (McMurphy) Cargill were sisters. Some of the Cargills were already in Boston in 1718.

The music background on this page is "The Gael" (Last of The Mohicans Movie Theme) played by the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards - Highland Cathedral. It can be turned off using the controls to the right >>

The Last of The Mohicans was James Robert Montgomery's favorite book when he was a boy (see "James Robert - Gentleman" page.)

Scots-Irish Emmigration . . .

Westward, William and Mary!

^ Early 1776 Map of Boston Harbor

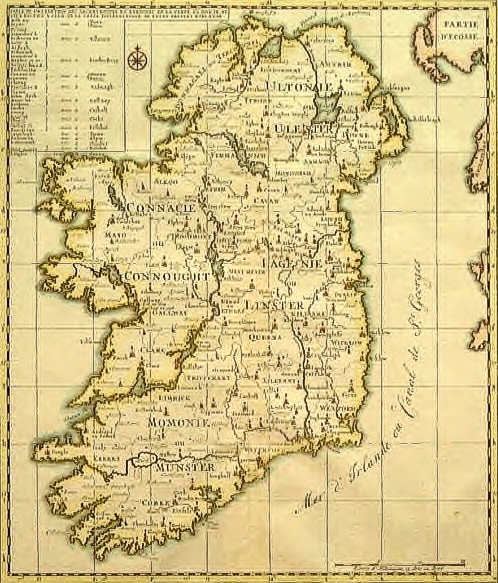

1719 Map of Ireland - blue circle is area of origin: Aghadowey / Antrim >

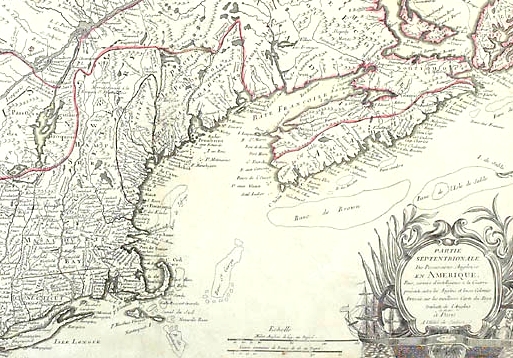

^ 1719 Map of The New World

^ Early Map of New England and Nova Scotia

^ An Old Irish Cottage /

Homestead near an

inlet from the Sea

Irish Brigantine Ship,

at port >

After three months at sea, the Ship

Maccullom (McCullum) sailed into

Casco Bay, Maine, arriving from

Boston, MA, September 22-29, 1718.

William and Mary and family lived in the

Merrymeeting Bay area until 1720, removing to Hopkinton, MA, after

many native Indian attacks and

massacres.

Their Settlement is noted as the

"Irish New Settlement" on Cyprian Southack's Map of 1720 (at right).

(Boston is due south)

^ "An Accurate Map of The Country 'round BOSTON in New England, from the best authorities", 1776.

Hopkinton is at left, just off the map (blue circle)

A Montgomery Family Genealogy

As recorded and developed by W.J. Montgomery

| ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||